Assertions on the nature of music

…And I would give you the gift of music that you might know your own soul. –Betty Kingsley Hawkins (prefatory quotation in ‘The Nature of Music’ by Maureen McCarthy Draper)

1. Music is an absolute, existing outside of Man, along with all the other abstractions assigned by him to The Great Everything (TGE) which is too vast and impenetrable to be truly known—except, perhaps, by the few who achieve Satori, Nirvana, or “enlightenment” as with a Bodhisattva. (Note: “TGE” is my construction for what others may call God, JHWH, Jehovah, Allah, etc.).

2. Each of us, I assert, is attuned to this element or aspect of TGE in various ways and degrees. I liken each of us as having differently constructed vibrating rods (or sets of rods) that respond to the universal music according to our individual resonances. Hence, some will find, throughout life and consistently, music from the Classical Period, exemplified by Haydn and Mozart, preferable to hip-hop, though the latter may be sometimes appealing.

3. Each of us, I assert, has ability in varying degrees to receive/perceive this universal music and to interpret it first, to oneself and second, to others.

4. A special few have the ability to represent this music in accepted notational form and, therefore, can concretize the music itself by the physical representation of it.

Music flows, from TGE-knows-where and –how, to a receiving human who, with the necessary skills, makes accepted musical notations on paper (or performs to give example) to represent what he perceives, along with written (or spoken) language remarks to more fully communicate it, e.g.: tempo rubato (as with Chopin), glissando, fortissimo, etc.

A performing musician reads these notations and transforms them through her nervous system to the instrument of her choice, for her own experience and that of others.

To summarize: music from God, to composer, to paper, to player, to audience.

Playing the Piano, in General, and Chopin’s Music in Particular

As to how much one needs to practice one’s instrument in order to remain fluent in it, the necessary amount and frequency varies, depending on one’s natural talents and physiology. Practice is not only playing compositions in one’s repertoire, but also exercises to keep the “drive train” of the pianist in harmony: eyes, brain, nervous system from brain to arms to hands to fingers, and a feedback system for instantaneous self-correction and adjustment. Ideally, these are not conscious efforts by the pianist. She develops these as a unity.

There are standard, two-handed exercises I have done in my younger life:

1. Scales for each of the twelve keys in an octave, running at least one octave

2. Single thirds, similarly, usually for two or more octaves

3. Double thirds, similarly

4. Arpeggios, similarly

5. Exercises developed by musicians through the centuries: Carl Czerny (one of Beethoven’s teachers), Charles-Louis Hanon, and John Thompson, among others.

Chopin is a special case: he “untied the octave”. His chords and other movements of the hand often reach beyond the octave. One needs a large and supple hand for those of Chopin’s pieces written in this manner. “Chopin invented many new harmonic devices; he untied the chord that was restrained within the octave leading it into the dangerous but delectable land of extended harmonies (NB: i.e., beyond the octave—R.P.). And how he chromaticized the prudish, rigid garden of German harmony, how he moistened it with flashing changeful waters until it grew bold and brilliant with promise (sic)” (Chopin: The Man and His Music, by James Huneker).

Chopin is a special case: he “untied the octave”. His chords and other movements of the hand often reach beyond the octave. One needs a large and supple hand for those of Chopin’s pieces written in this manner. “Chopin invented many new harmonic devices; he untied the chord that was restrained within the octave leading it into the dangerous but delectable land of extended harmonies (NB: i.e., beyond the octave—R.P.). And how he chromaticized the prudish, rigid garden of German harmony, how he moistened it with flashing changeful waters until it grew bold and brilliant with promise (sic)” (Chopin: The Man and His Music, by James Huneker).

Absolute and Program Music

Haydn’s music is, for the most part, absolute music. Mozart did compose a greater proportion of program music than did Haydn, by my reckoning. Chopin continued the trend toward program music that generally occurred in the Romantic Period during which Chopin lived.

The performer, and the listener, will experience different emotions and sensations when listening to absolute vs. program music.

Here is how I respond to these two types:

Absolute music (take any Brahms symphony) will cause my chest to swell and tears to form for no definable reason, except that the music strums my “vibrating rods” (see above) in ways that render me helpless to do otherwise. It’s very much like the sensations I have had upon observing the births of two of my children and of one of my grandchildren.

Absolute music (take any Brahms symphony) will cause my chest to swell and tears to form for no definable reason, except that the music strums my “vibrating rods” (see above) in ways that render me helpless to do otherwise. It’s very much like the sensations I have had upon observing the births of two of my children and of one of my grandchildren.

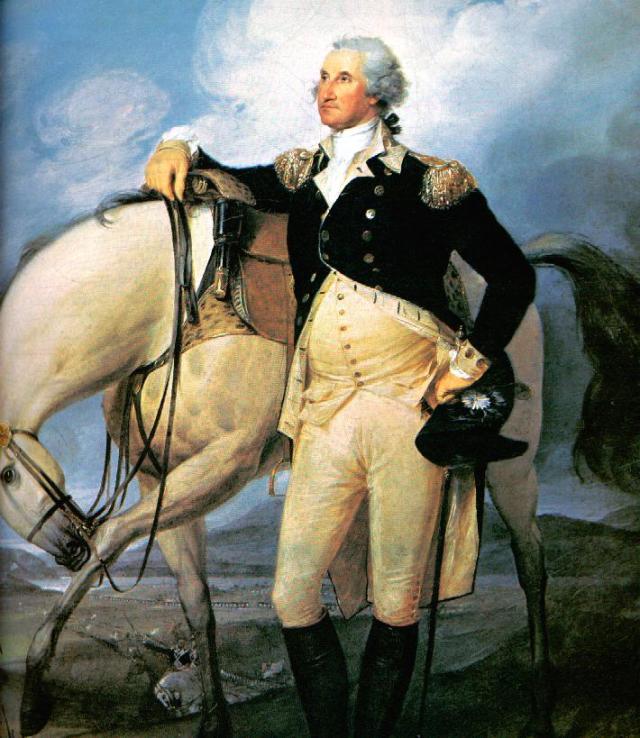

Program music, on the other hand, will invoke more definable feelings: patriotism (Chopin’s Polonaises, any good march, Sibelius’s Finlandia), pastoral and nature visions (Beethoven’s sixth symphony, almost all of Ralph Vaughn Williams, much of Frederick Delius), the sweet melancholy of imagining the ending of a long and good life (The Lark Ascending by Ralph Vaughan Williams), etc.

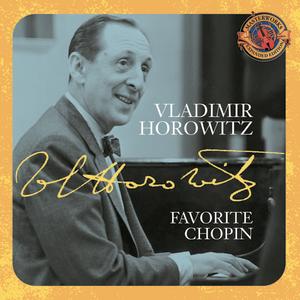

Chopin’s Raindrop Prelude is a solid example of program music. It’s about the soft beginning, tumultuous middle and fading ending of a storm, with an incessant note reminding us of the raindrops on a window sill, or on whatever is in the imagination of the listener. Vladimir Horowitz playing Chopin’s “Raindrop” Prelude, Op 28 No 15, in D Flat Major.

Chopin’s Raindrop Prelude is a solid example of program music. It’s about the soft beginning, tumultuous middle and fading ending of a storm, with an incessant note reminding us of the raindrops on a window sill, or on whatever is in the imagination of the listener. Vladimir Horowitz playing Chopin’s “Raindrop” Prelude, Op 28 No 15, in D Flat Major.

Your character’s Mozart and Haydn pieces will be, unless marches or waltzes, absolute music, eliciting from her (or developing in her) the broadest, most eternal, let us say ‘religious’ feelings.

In imagining a pianist’s feelings, overall, while she is performing, I imagine she is in the “zone” or in the “flow” that athletes and other performers achieve when all physical and other attributes are in synchronization during a well-rehearsed and challenging event.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

The above is an attempt to capture, in words, the ineffable nature of music and its affect on and in humans.