… and why am I dwelling upon this question?

I, once again, have decided not to renew my subscription to the New York Review of Books (NYRB).

I admit to a growing prejudice against those who publicly accept the label “intellectual.” However this appellation is to be translated into ordinary language, those who consciously and conspicuously carry it apparently deem themselves and their ilk better than those who do not warrant the label.

I think, in particular, of the editors and (not all) writers in such literary journals as the NYRB and the London Review of Books. I have not recently read either Harper’s or The Atlantic, although there are times I am tempted to buy a copy from a newsstand at an airport. The writing and especially the editorializing, in too many instances for me, is presented with pompous assuredness that their respective views of the world are the only ones worth holding and that all dissenters are, most charitably, ignorant or, least charitably, uncivilized.

It’s quite annoying, and I am moved to get other opinions about what it is to be “intellectual” to either buttress my prejudice or to dispel it.

Intellectual (Wikipedia):

An intellectual (from the adjective meaning “involving thought and reason“) is a person who tries to use his or her intelligence and analytical thinking, either in their profession or for the benefit of personal pursuits.

“Intellectual” can be used to mean, broadly, one of three classifications of human beings:

1. An individual who is deeply involved in abstract erudite ideas and theories.

2. An individual whose profession solely involves the dissemination and/or production of ideas, as opposed to producing products (e.g. a steel worker) or services (e.g. an electrician). For example, lawyers, accountants, professors, politicians, entertainers, and scientists.

3. Third, “cultural intellectuals” are those of notable expertise in culture and the arts, expertise which allows them some cultural authority, which they then use to speak in public on other matters.

Here is what I derive from the above definition:

- An intellectual uses (or tries to use) analytical thought, intelligence and reason in his or her pursuits.

My comment: Who doesn’t, at least to some degree? And, how should one label a person who presumably doesn’t meet these criteria? I reject this portion of the definition.

- A person engaged primarily in the production and manipulation of ideas as distinct from tangible objects.

My comment: this has the ring of truth in it. An intellectual has a tendency or preference to live in a world of abstractions. I like it because it is clear and non-judgmental.

- A subset of those who prefer abstractions is called “Cultural Intellectuals.” These people accrue public authority through some means unavailable to most others and are considered by many people as “experts.”

My comment: This is a special set of human beings, many of whom we see giving public lectures and most often as talking heads on television. They also write a lot of opinions in literary journals (such as those mentioned above) and in politically-oriented journals and newspapers. Some of these are people who locate themselves primarily in institutions of higher learning and think tanks.

Now on to another set of definitions to see if I can discover more useful ideas.

in⋅tel⋅lec⋅tu⋅al –adjective

1. appealing to or engaging the intellect: intellectual pursuits.

2. of or pertaining to the intellect or its use: intellectual powers.

3. possessing or showing intellect or mental capacity, esp. to a high degree: an intellectual person.

4. guided or developed by or relying on the intellect rather than upon emotions or feelings; rational.

5. characterized by or suggesting a predominance of intellect: an intellectual way of speaking.

–noun

6. a person of superior intellect.

7. a person who places a high value on or pursues things of interest to the intellect or the more complex forms and fields of knowledge, as aesthetic or philosophical matters, esp. on an abstract and general level.

8. an extremely rational person; a person who relies on intellect rather than on emotions or feelings.

9. a person professionally engaged in mental labor, as a writer or teacher.

My comment: Most of the above is tautological and, therefore, useless. What does ring out clearly is the notion of superiority: rationality vs. emotionality, the placing of high value on complexity vs. (by inference) simplicity, and, as in the previous definition, the placing of high value on abstract thinking vs. (by inference) concrete thinking or doing. Writers and teachers are singled out as candidates for being intellectual. I’m getting nervous now—I am beginning to see myself forming in this abstract ooze.

After Gulliver’s ship is attacked by pirates, he is marooned near a desolate rocky island, near India. Fortunately he is rescued by the flying island of Laputa, a kingdom devoted to the arts of music and mathematics but utterly unable to use these for practical ends.

It’s very likely, given Swift’s way of satire, that he was well aware of the Spanish meaning (“the whore”); Gulliver himself claimed Spanish among the many languages in which he was fluent. Some find a parallel with Martin Luther’s famous quote “That great whore, Reason”, given Laputians’ extreme fondness of reason. However, that Swift’s intention was to mock the so-called “Age of Reason” is not without doubt, given the story-teller’s great admiration of Houyhnhnms for their rational thinking. Source

OK, last set of definitions for “Intellectual”:

US Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary

•noun The intellect or understanding; mental powers or faculties.

•adj Belonging to, or performed by, the intellect; mental; as, intellectual powers, activities, •etc.

•adj Relating to the understanding; treating of the mind; as, intellectual philosophy, sometimes called “mental” philosophy.

•adj Suitable for exercising the intellect; formed by, and existing for, the intellect alone; perceived by the intellect; as, intellectual employments.

•adj Endowed with intellect; having the power of understanding; having capacity for the higher forms of knowledge or thought; characterized by intelligence or mental capacity; as, an intellectual person.

My comment: Again, there is much that is tautological here. The new thought or phrase is “having capacity for higher forms of knowledge …” Aha! “Higher.” This relates back to my original complaint. The clear implication is that abstract stuff is “higher” than concrete stuff and, therefore, people who can successfully carry around the label “intellectual” are higher-order human beings than those who cannot carry this label successfully, or who do not give a rat’s patoot if they do or do not carry it.

Here is a definition that provides another new notion:

Intellectualism

The Ism Book

1. (ethics) The view that knowledge is sufficient for excellence — that a person will do what is right or best as a result of understanding what is right or best; sometimes also called Socraticism.

2. (approach) Another term for rationalism* or scholasticism.

3. (epistemology) Specifically, a tradition of philosophy in the 17th and 18th centuries that emphasized deductive reasoning and focused on the “hard” branches of philosophy (e.g., epistemology) instead of the value branches (e.g., ethics, politics, and aesthetics); the most prominent rationalists were Descartes (1596-1650), Leibniz (1646-1716), and Spinoza (1632-1677). More generally, any philosophy that is overly deductive and attempts to mold reality to fit its theories rather than the other way around.

My comment: I feel we are now at the heart of the matter: “knowledge is sufficient for excellence;” “attempts to mold reality to fit…theories rather than the other way around.” Considering myself a rational person, I certainly have no issue with a rational approach to discussing any issue or in the doing of anything concrete. My issue is with the implicit or explicit position of any presenter that he or she possesses absolute knowledge of the facts and their true interpretation.

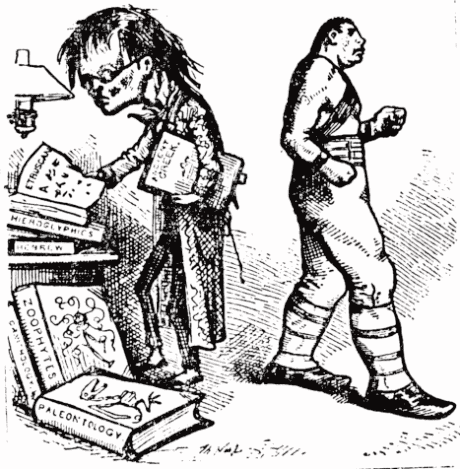

An intellectual contrasted with a prize-fighter; by Thomas Nast ca. 1875. His caricature encapsulates the popular view that sees reading and study as being in opposition to sport and athletic pursuits, although the bovine figure of the fighter is no less negative than that of the scholar. (Wikipedia)

Last, I want to see how others who may share my prejudice are defined:

Anti-intellectualism

Anti-intellectualism describes a sentiment of hostility towards, or mistrust of, intellectuals and intellectual pursuits. This may be expressed in various ways, such as attacks on the merits of science, education, art, or literature.

Anti-intellectuals often perceive themselves as champions of the ordinary people and egalitarianism against elitism, especially academic elitism. These critics argue that highly educated people form an isolated social group tend to dominate political discourse and higher education (academia).

Anti-intellectualism can also be used as a term to criticize an educational system if it seems to place minimal emphasis on academic and intellectual accomplishment, or if a government has a tendency to formulate policies without consulting academic and scholarly study.

OK, enough with definitions already. As I have stated elsewhere in this journal, “all words are lies;” they cannot adequately substitute for the experience of the moment.

I will relent at this point to offer an olive branch to any person, whether having donned the label intellectual or not, regarding the proper way to argue an issue—if only he or she is open to hear and consider my position, as well.

The people I have no patience with, and these appear in the pages of the journals referenced above, are those who come from an ideological position. That is, they “know” that they know how the world is or should be constructed and will use any words or “fact” to fit their prejudices. Worse, they have no ability to hear and use observable, or at least arguable, facts that are counter to their position. These people have no claim to the label intellectual. They are not arguing from a rational position, but from an emotional position. There is nothing wrong and myriad things right about emotion and emotions, but not in a rational argument. Intellectual means rational. See above.

The people I have no patience with, and these appear in the pages of the journals referenced above, are those who come from an ideological position. That is, they “know” that they know how the world is or should be constructed and will use any words or “fact” to fit their prejudices. Worse, they have no ability to hear and use observable, or at least arguable, facts that are counter to their position. These people have no claim to the label intellectual. They are not arguing from a rational position, but from an emotional position. There is nothing wrong and myriad things right about emotion and emotions, but not in a rational argument. Intellectual means rational. See above.

I reject, for myself, all labels that have the suffixes “-ism,” “-ist” and “-ian”. To accept such would be to limit my universe to those ideas and concepts contained in the boxes these suffixes imply. And, certainly, I am not a totalitarian.

“Get your facts first, and then you can distort them as much as you please.” —Mark Twain

It is always useful to see the waters we are swimming in—that is, what is usually invisible to us—from the perspective of one who swims in several other, and different, waters. My summary here is not comprehensive and must be read with some skepticism since my written notes are incomplete. But I have buttressed some of Mr. Donner’s key points by correlating them with what I have found on the Internet.

It is always useful to see the waters we are swimming in—that is, what is usually invisible to us—from the perspective of one who swims in several other, and different, waters. My summary here is not comprehensive and must be read with some skepticism since my written notes are incomplete. But I have buttressed some of Mr. Donner’s key points by correlating them with what I have found on the Internet. In addition, according to Mr. Donner, the Swedish system is based heavily on the philosophy of

In addition, according to Mr. Donner, the Swedish system is based heavily on the philosophy of