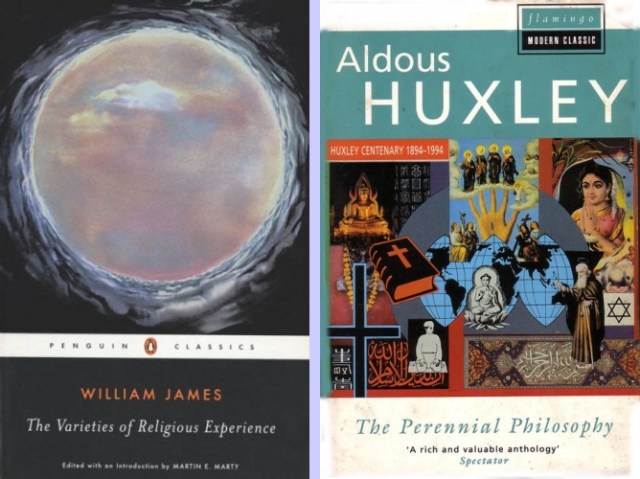

There are two teachings which deserve a reading in high school, perhaps, but certainly in one’s young adulthood: The Perennial Philosophy, by Aldous Huxley, and The Varieties of Religious Experience, by William James. I did not read these until I was in my 70s and regret not having read them earlier.

Written during the first half of the 20th Century, they intersect and complement each other in many places. One place they intersect is at the subject of “charity.”

Having now read these books I now see charity as an easily misunderstood word and concept, or at least one as being variously, inconsistently interpreted. Before reading these books I perceived charity as a neutral, slightly religious term, while my wife Eva finds it a distasteful one, connoting a relationship of superiority of one person over another (e.g., the giver and the receiver of alms).

But this discussion, so far, is off the mark; it is not addressing the fuller, more soulful original meaning of the concept of charity.

According to Huxley, the ‘perennial philosophy’ is:

the metaphysic that recognizes a divine Reality substantial to the world of things and lives and minds; the psychology that finds in the soul something similar to, or even identical with, divine Reality; the ethic that places man’s final end in the knowledge of the immanent and transcendent Ground of all being…Rudiments of the perennial philosophy may be found among the traditional lore of primitive peoples in every region of the world, and in its fully developed forms it has a place in every one of the higher religions.

In Chapter 5, “Charity,” Huxley writes:

By a kind of philological accident…the word ‘charity’ has come, in modern English, to be synonymous with ‘almsgiving,’ and is almost never used in its original sense, as signifying the highest and most divine form of love…(C)harity is disinterested, seeking no reward, nor allowing itself to be diminished by any return of evil for its good…(P)ersons and things are to be loved for God’s sake, because they are temples of the Holy (Spirit)…The distinguishing marks of charity are disinterestedness, tranquility and humility. But where there is disinterestedness there is neither greed for personal advantage nor fear for personal loss or punishment…

As for Varieties, Wikipedia describes the book thus:

A Study in Human Nature…by the Harvard psychologist and philosopher William James that comprises his edited Gifford Lectures on “Natural Theology” delivered at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland between 1901 and 1902. These lectures concerned the nature of religion and the neglect of science, in James’ view, in the academic study of religion. Soon after its publication, the book found its way into the canon of psychology and philosophy, and has remained in print for over a century.

James has this to say about charity in his chapter on “Saintliness,” which condition elicits these “practical consequences:” asceticism, strength of soul, purity and charity. Regarding the latter, he writes: “The shifting of the emotional center (toward loving and harmonious affections) brings…increase of charity, tenderness for fellow-creatures…The saint loves his enemies, and treats loathsome beggars as his brothers.”

“…Charity and Brotherly Love.. have always been reckoned essential theological virtues…But these affections are certainly not mere derivatives of theism. We find them in Stoicism, in Hinduism, and in Buddhism in the highest possible degree.”

I found no passage where James, like Huxley in a later time, harked back to an earlier and more apt understanding of the nature of the concept of charity. I take this to mean that the general understanding of the English word in James’s time had not yet made the lamentable change to which Huxley refers.

What is there to glean from this brief exposition on “charity?”

First, I see no essential difference regarding the subject between these two great thinkers.

Second, I see that Huxley’s lament that we have lost the original meaning is importantly true, at least for me.

Neither of these writers was a religionist nor a proselytizer of any creed or faith. Yet, each seemed quite comfortable in quoting from many creeds; and, each shows us most creeds teach that we are innately holy and we should relax and allow our holiness to be manifest.

I conclude that charity resides in one’s soul and is realized by one’s loving actions toward others.